Andy Ralph

Arcana

Cat Snodgrass

Chris Beeston

Clynton Lowry

Cynthia Brothers by Nick Parker

David Bordett

David Kennedy Cutler

Deville Cohen

Dylan Ahern

Gail Burr

Halsey Rodman

Imaan Sattar

Jeff Williams

Josephine Halvorson

Mac Collins

Malcolm Ransome

Marie Lorenz

Max Heiges

Michael Joo

Oscar Bedford

Patrick Carlin Mohundro

Permanent Maintenance Studio

Peter Brock

Philippe Malouin

Phyllis Baldino

Pooneh Maghazehe

Raul De Lara

Roman Cochet

Rudolf Samohejl

Sara Greenberger Rafferty

Sarah Burns

Sarah Oppenheimer

Scott Nadeau

Serra Victoria Bothwell Fels

Shaun Krupa

Wyatt Burns

Yasue Maetake

Zachary Besner

Zak Kitnick

Installation view including works by Josephine Halvorson, Yasue Maetake, and Jeff Williams.

David Bordett, Lower Than Below (even the bluest sky changes hue at night), 2023

Serra Victoria Bothwell Fels, Honest Bodies, 2022

Shaun Krupa, Untitled (airplane 2), 2018

Jeff Williams, Oxidation Table, 2013-2014

Oscar Bedford, Pegboard Painting, 2019-23

Max Heiges, Tall Chairs, 2023

Wyatt Burns, Japanese-American Saw, 2015

Zachary Besner, Solid Hollow Table, 2021

Installation view including works by Josephine Halvorson, Pooneh Maghazehe, Yasue Maetake, Andy Ralph, and Zachary Besner.

Zak Kitnick, Wall One, Wall Two, Wall Three, Wall Four, 2017

“I very vividly in memory fall in love with my past lovers—as carrier of the sunmessage—as meaning of all-system: ‘perpetual screw!’ I see—how perishable they themselves were—how deteriorated in care and affection by time—as earthly things will—until they become dull mechanics—which I did not let suffer to happen—hence my utter loneliness—and had I understood more of the—outer life mashinery [sic] appertaining to emotion—to give it practical possibility—I should—and very plentifully at least could—have provided against such time as now.”

Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Letter to Djuna Barnes, University of Maryland Libraries. c.1924–1927.

For the second exhibition at International Objects, our focus turns to artworks that position tools and hardware as their subject. The veneration of (and corresponding trepidation towards) new technologies has been a constant throughout history across civilizations. The tools and materials devised by each generation represent a seemingly magical extension of human power, making inroads into the erstwhile realms of the divine.

The fruits of the industrial revolutions of Europe were showcased by revolutionary and imperial powers alike through spectacular exhibitions of new technologies. The Exposition des produits de l’industrie française was a celebration of French technology held from 1798 to 1849 that offered “a panorama of the productions of the various branches of industry with a view to emulation.”¹ In 1851 the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations was held in a Crystal Palace built for the occasion that allowed Britain to assert its superiority as a colonizing empire “in almost every field where strength, durability, utility and quality were concerned, whether in iron and steel, machinery or textiles.”² The display of technologies, as evidenced by the history of exhibitions that have captured them, is a meaningful conflation of modernism with modernity.

As a counter-response to these showcased technologies, artists and artisans revalued handcraft for its distinctive presence against the standardized objects yielded by new machinery. An Arts and Crafts movement emerged in the second half of the 19th century as a riposte against the seizure of modes of production by emergent factory-style industrialization. Using tools with the added awareness of their symbolic potential, artists gave value to the materials and processes that were often the subject of the work itself.

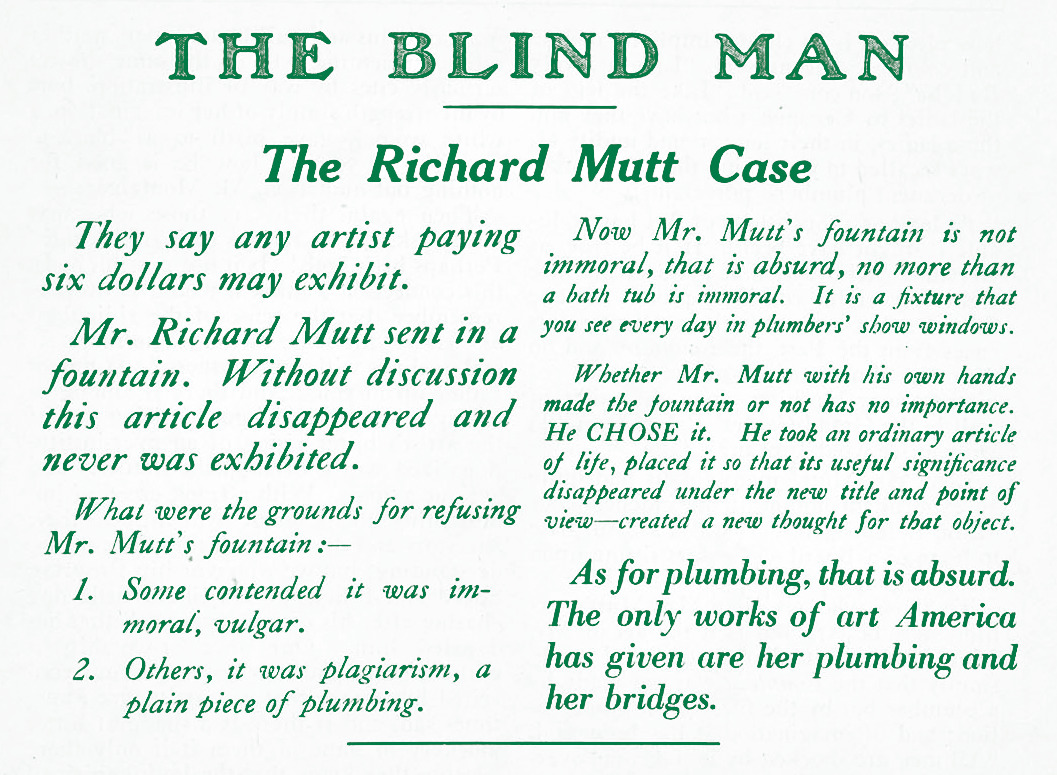

These dynamics were all at play in 1917 when an exhibition to be hosted by the Society of Independent Artists in New York was being organized. Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven had sent an upended urinal, entitled Fountain, from Philadelphia to New York to Marcel Duchamp who subsequently submitted it for inclusion in the exhibition. The piece, produced by J. L. Mott Iron Works and later inscribed with the male pseudonym of the Baroness “R. Mutt,” was unceremoniously rejected by the “unjuried” exhibition selection committee prompting Duchamp, a ‘friend’ of the Baroness, to resign from the group and bring the piece to the 5th Avenue studio of Alfred Stieglitz, where it was photographed and then lost or destroyed. In an article that appeared in the Dadaist journal The Blind Man following the exhibition³ (which also included Stieglitz’s documentation of Fountain), the editors came to the defense of Richard Mutt:

That same year, Baroness Elsa produced a similar sculpture comprised of a cast iron plumbing trap mounted atop a wooden miter box.⁴ The work, entitled God, positions common hardware as a physical manifestation of the divine. Although this particular deification of vernacular hardware represented a paradigmatic shift in the art discourse of the time, the veneration of objects in such exhibitions had a history that preceded it. Regained was a connection of tools and hardware to the ethereal realms not unlike the synthesis of Vitruvius or Hero of Alexandria.⁵

Tools and hardware both express the objects that they are capable of producing and reflect the teleological expression of their user. When artists are presented with a hardware store, the store itself operates as an interface of sensible outcomes for the formation of their work. At times, the tools and materials take on an iconographic or political role or are themselves an emulation of the artists’ labor or action. Or, per Baroness Elsa, hardware can be elevated to create a dogmatic vision—based in the material world where the imposition of an ordinary thing can “create a new thought for that object” akin to the gestural manipulations of a spiritual power.

1 Anne Dion-Tenenbaum, “Un âge d'or des arts décoratifs. 1814-1848”, from the catalog of October-November 1991 Grand Palais exhibition, Paris, 1991.

2 Yvonne Ffrench, “The Great Exhibition”, 1851, London: Harvill Press, 1950.

3 Anon., “The Richard Mutt Case,” The Blind Man, edited by Henri-Pierre Roche, Beatrice Wood, Marcel Duchamp, New York, no.2, May 1917.

4 A work “currently not on view” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

5 Both Vitruvius (c.80–70 BC–after c.15 BC) and Hero von Alexandria (c.60 AD) were thinkers of classical antiquity who connected tools and building materials with the exploits of the divine. See Vitruvius “De architectura” or Hero von Alexandria “Treatise on Pneumatics”. An interesting note, the word pneumatics, here relating to air powered tools and instruments, takes its prefix from “pneuma” meaning “wind” or “breath” that (in Stoic thought) dually signified the spirit, soul, or creative force of a person.

International Objects

53 Scott Ave, Brooklyn, NY

info@objects.international

+1 424-OBJECTS

Subscribe to our email list: